If a tree fell in a forest and nobody was around to hear it, did it actually make a sound? Following this philosophical thought experiment, the multi-screen video installation If a Tree Fell in a Forest triggers the question whether perpetratorship we are not aware of, matters. In a time of growing right-wing extremism, Redpilled, Public Enlightenment, A Mirrored Image, and In the Blue deal with ignorance, the accessibility of perpetrator narratives, as well as generational and cultural gaps.

The works were produced within the scope of Houses of Darkness (2020-2023), an online cooperation co-funded by Creative Europe and a joint initiative of three WW2 memorial centres reaching out to a young audience: Bergen-Belsen Memorial (DE), Camp Westerbork Memorial Centre (NL), Falstad Centre (NO) and Paradox. In 2021 and 2022, Ganslmeier and Zibelnik visited the remains of the commander’s houses at the three sites. In the resulting works, they question the perpetrator’s perspective and share their experiences online and in exhibitions with the (young) public.

In addition to the works mentioned above, the travelling exhibition If a Tree Fell in a Forest can be extended with Haut, Stein – an extensive photographic story about the process of deradicalisation or exiting an extremist movement. Between 2017 and 2022, Ganslmeier worked in close cooperation with EXIT Germany, an organisation assisting individuals in leaving the right-wing extremist scene. In contrast with Redpilled or Public Enlightenment which warn against the current threat of online radicalisation, Haut, Stein stands as an essential counterweight, showing that no matter how lengthy or challenging the process might be, there is a way out of an extremist movement.

About the works

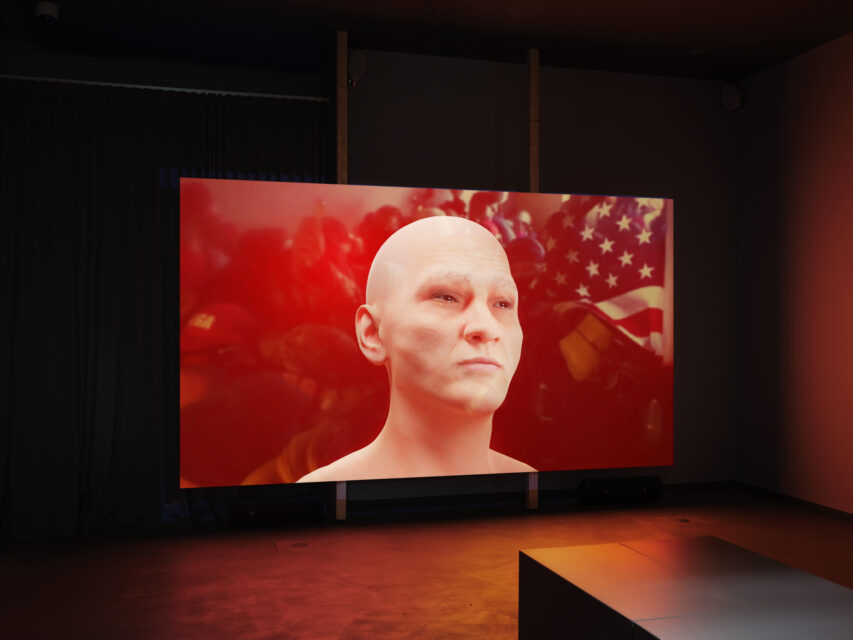

Redpilled is a story about the spread of alt-right ideology and its close correlation with the global rise of meme culture. Told from the perspective of Wojak (lit. soldier) — a hugely popular meme character known for its versatile ability to lend itself to a number of human stereotypes – the work delves into the dangerous humour and fascination with violence perpetuated by memes. Throughout the work, references are made to recent terror attacks, such as the Christchurch shooting, drawing a direct connection between the seemingly harmless online environment of nihilism and its violent ‘real-life’ consequences.

Public Enlightenment is a series of three distinct representations of perpetrator perspectives: fictional (Hollywood), historical (WWII archival material), and contemporary (Youtube). The corresponding three channels of the installation piece, Common Enemy, Strong is Beautiful, and War Room interrogate the sources of today’s far-right extremist ideas.

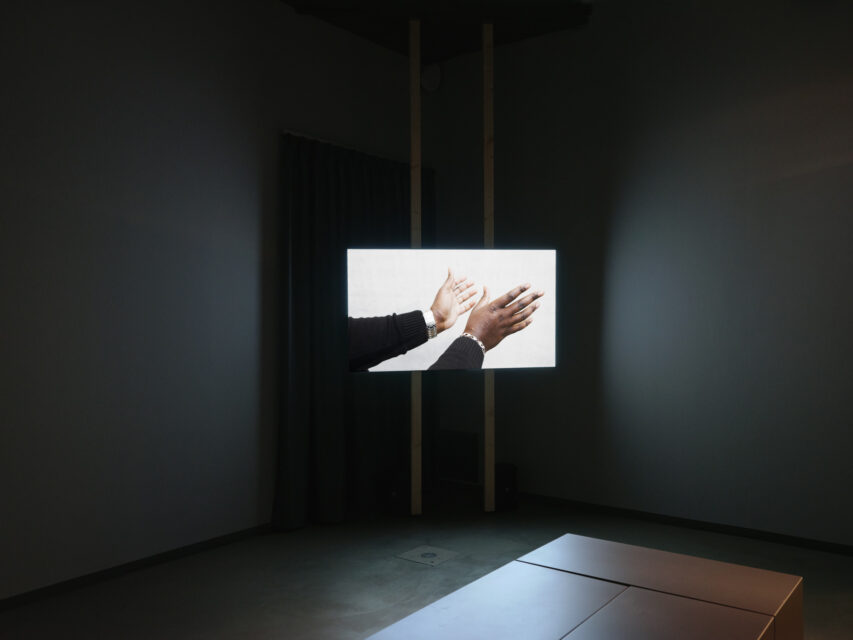

A Mirrored Image refers to the different interpretations of the Holocaust that exist in today’s European population. Who and what shapes the image and the legacy of a former concentration camp? Filmmaker Jakob Ganslmeier grew up in Dachau, Germany, close to the former concentration camp which is now a memorial centre, while spoken word artist Onias Landveld grew up in Suriname (later in the Netherlands) and had never visited a concentration camp memorial before. ‘My imagination was trained by Hollywood’, Landveld says in the piece, referring to the numerous representations and mediations of the Holocaust he consumed in his youth. The crimes of colonialism directed his imagination of the atrocities committed by the Nazis when roaming the empty spaces of Bergen-Belsen and the still-active military training grounds surrounding it: ‘My imagination is black’. The resulting work brings together their radically different perspectives while opening up new questions: What is the relationship between the Holocaust and post-colonial discourse? Can the two eventually be brought into dialogue?

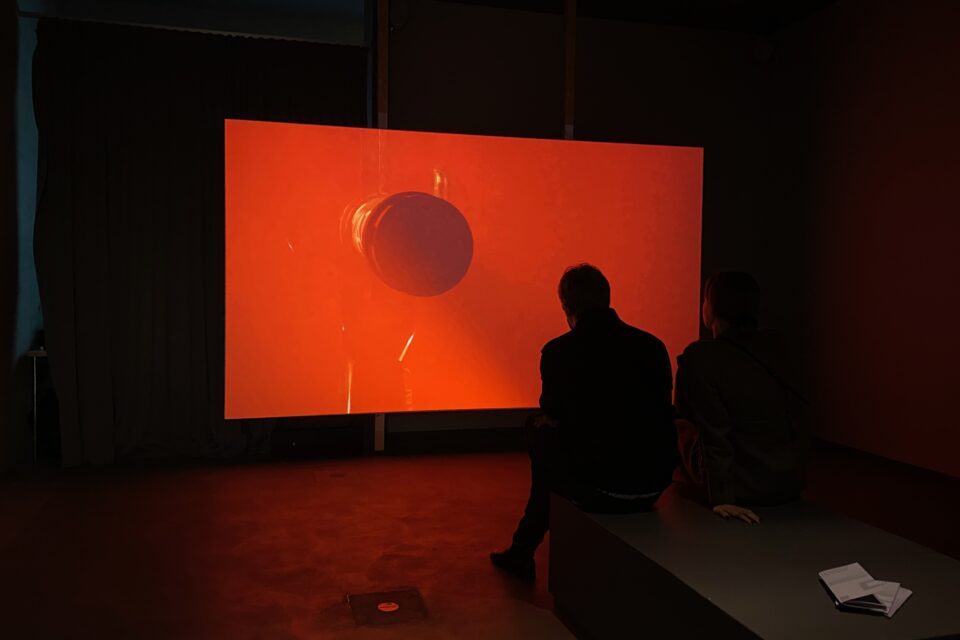

In the Blue is a video work in which a Norwegian amateur choir, standing on a jetty in the Trondheimfjord, performs an SS song. Had they not been asked to do so by the artist, Jakob Ganslmeier working in collaboration with the Falstad Centre, the friendly singers – who were aware of the song’s origin – would never have sung it. They were, however, free to decline repeating it.

We know that while SS Strafgefangenlager Falstad – as it was called at the time – was operational, villagers from Ekne helped prisoners by smuggling in food and medicine. What does it mean when the Ekne choir sings the SS song today? Their singing cannot be regarded as an ideological statement. Still, it poses the question: How long should it take for us to let go of our local past?

Haut, Stein focuses on National Socialist symbology which remains visible to this day. It interrogates the persistence, use, and obliteration of these signs in two distinct formats: as the structural ornaments and architecture through which the symbols of National Socialism linger in public space; and as tattoos, by which the same signs serve to reaffirm an individual’s commitment to right-wing extremism. Former neo-Nazis are portrayed in the process of departing from their previous identities as right-wing extremists. The photographs show tattoo removals or cover-ups, as symbols that for years expressed an identity and a political worldview disappear slowly. The erasure of signs inscribed into the skin is a very deliberate step for those leaving; it is costly, lengthy and painful.

Meanwhile, monochrome photographs depict historical NS symbols which remain visible at numerous outdoor locations. Despite the process of denazification and attempts at removal, these signs or their traces remain visible in a range of locations; on houses, in decorative bands and in facades. Ganslmeier’s images reveal those fragments as well as examine their wider spatial context in villages, streets and settlements.

By situating these individual stories into a socio-political context, this work poses the question: to what extent is the German past really past?

Ana Zibelnik (1995) is a photographer currently based in the Netherlands. She graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts and Design in Ljubljana in 2018 and recently completed her MA degree in film and photographic theory at Leiden University. Through long term projects she explores the topics of death, immortality as well as the relationship between photography and extinction.

Ana Zibelnik (1995) is a photographer currently based in the Netherlands. She graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts and Design in Ljubljana in 2018 and recently completed her MA degree in film and photographic theory at Leiden University. Through long term projects she explores the topics of death, immortality as well as the relationship between photography and extinction.